*** We believe communicating with our clients is of utmost importance, especially during turbulent times in the market. While we don’t claim to have a crystal ball on the future of any financial market at a given point in time, we do believe that keeping clients informed on why things are happening increases their comfort level and understanding. This post contains a message initially sent to clients after a terrible September 2011 and in the escalation of the European sovereign debt crisis as part of that communication effort***

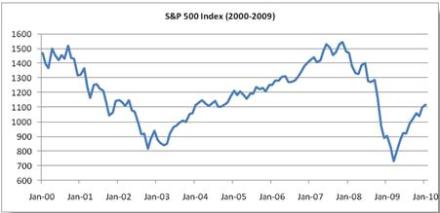

Many of you will remember my messages at the beginning of Q3 which indicated that the Fed-provided updraft in financial markets was likely behind us with the end of their Quantitative Easing program as well as my fears about what seemed to be a troubling situation in European government debt (specifically Greece). I pointed out that despite 7-8 consecutive quarters of seeing account balances move up, you should be prepared for more typical up-and-down quarters to come. Those issues in Europe have intensified and put pressure on markets around the world as you’ve undoubtedly heard and noticed by now. U.S. stocks, as measured by the S&P 500 were down almost 14% for the quarter. Small-cap U.S. stocks and international stocks were down over 20% for the quarter with some sectors and emerging markets fairing even worse. Consequently, you will see that your account balances for aggressive portfolios have fallen along the same lines in Q3, while more conservative portfolios have had a more muted response, but have fallen nonetheless. Each day, and often multiple times per day, I ask myself if the fall in stocks is appropriate given the circumstances in the global economy. Should we be getting more aggressive because the markets have overpriced the probability of a global recession and another credit crisis led by Europe’s woes? Should we be getting more conservative because the markets haven’t priced in that probability enough? As I’ve discussed with all of you in the past, I believe that markets are generally extremely good at processing information and letting the aggregate intelligence of millions of participants determine the right price for a given security and the market as a whole. While there is sometimes misalignment for spectacular reasons, I don’t think we have that misalignment right now.

World economies have problems, very big problems, especially in Europe. Their government debt issues have the capability to bring down banks like our mortgage problems brought down banks here in 2008. If European banks fail, a chain of events will take place which will spill over to the U.S. in multiple ways. First, Europe as a whole is a bigger economy than the U.S. So many of our companies do a significant portion of their business in Europe. If Europe slows, so will those companies. Second, many U.S. banks own assets that derive their value in one way or another from European companies and countries. Those assets will fall in value, putting the same kind of strain on our banking system as it faced when mortgage assets fell in value. Third, the U.S. dollar will likely strengthen vs. European (and other global) currencies via a safety / liquidity trade. This will hurt U.S. exports and especially when combined with the bank issues which will make credit harder to obtain, it will stop any recovery we’re seeing dead in its tracks. As the probability of a Greek default rises, unless there is a credible plan in Europe to stop the chain of events (think dominos falling) that would occur because of it, values of markets around the world will fall. Along those same lines, as the probability of a Greek default falls, or containment plans that would stop the domino effect emerge with more credibility, markets rise. This impacts global markets in that they all begin to move in the same direction at the same time and, depressingly, that impact swamps the impact of individual company, industry, or even country performance.

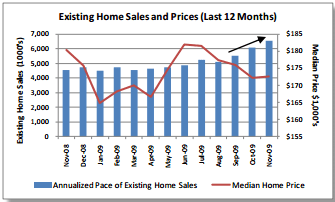

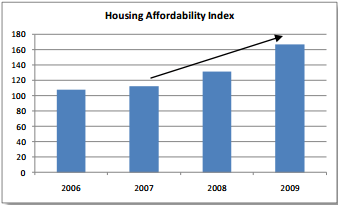

The situation in Europe seems grave, but there are a few underlying mitigating factors that are seldom discussed. Companies have gone through major cost cutting in the last three years and have increased their own emergency funds drastically. In aggregate they have almost double the cash on hand than they did in the 2008 downturn which leaves much more room to survive another downturn without severe additional cost cutting and layoffs. Banks have been recapitalized and continue to be supported by lending programs from the Federal Reserve, lowering the odds of another Lehman-like failure dramatically from where it was pre-Lehman. Consumers have been paying down debt rather than taking on more of it over the last few years. House prices have continued to fall (yes, I’m calling that a good thing for the future even though it has been a bad thing for homeowners to date), while mortgage rates are at historic lows (30-year fixed avg’d 3.94% last week!!). Housing is the largest expense for most of people, and it hasn’t been this cheap in decades. Energy prices continue to move with the economy, softening the blow of a slow down with reduced prices for heating this winter and at the pump where many areas in the country have seen a 20% reduction in gas prices over the past few months.

My conclusion to all of this is that the market seems to have appropriately priced the risks that are present in the global economy. It’s also appropriately pricing in the fact that companies and individuals are more capable of handling an economic slowdown than they have previously been. It will continue to operate on a binary level, Europe’s looking better – the world’s not ending – stocks up… vs. Europe’s looking worse – we’re all doomed – stocks down. Eventually, governments and federal reserves will stop taking the headlines and company productivity and innovation will win it back. Until then, expect the volatility to continue, again, in both directions, and with all but the safest of asset classes moving in tandem.

We’re of course taking advantage of this volatility in two ways. One, through rebalancing, selling bonds (which have generally increased in value through the turmoil), and buying stocks (which have fallen) to re-establish the stock/bond ratio that is appropriate for your goals. When the market turns around, you’ll have more stock than you would have which means you’ll gain more than you would have, allowing us to sell stocks and buy bonds again to re-establish the proper ratio. This provides for a natural, non-emotional, buy low / sell high rhythm to the portfolio. Second, where possible, we’re beginning to take advantage of losing positions by selling them, realizing the capital loss, and reallocating the money in similar assets. This process, called “tax-loss harvesting”, allows us to capture the loss for tax purposes, either offsetting other gains in your portfolio, or allowing you to take a deduction for losses on your 2011 taxes, all while leaving your exposure to the asset the same so you’ll benefit when the market starts to rise again.

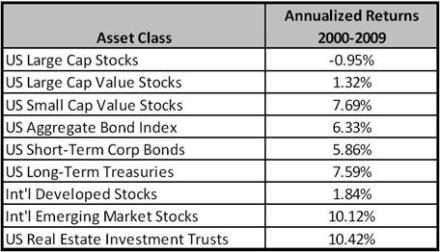

So what does this all mean to you? Well, it means that nothing has really changed from a financial planning standpoint. Your emergency fund money is in cash and continues to protect you in the case of an emergency. Money for short-term goals is protected in lower-risk portfolios with a higher percentage of short-term, high quality bonds that continue to pay interest though a downturn. Money for long-term goals is exposed to the short-term whims of the market in exchange for the likely higher average returns that will be earned over the long-term. In reality, long-term money is better off if the market would stay low for a while and let individuals get more into it before it rises over the long-term.

As long as the emergency fund is big enough (but not too big to impact your ability to fund future goals)… as long as the short-term portfolio is consistent in size with what’s needed for your short-term goals… and as long as the long-term portfolio is defined properly (i.e. you’ve communicated your lack of need for that money in the short-term properly)… then your ability to achieve your goals remains intact despite the stock market’s past quarter of performance. As always, I encourage you to communicate with me whenever something changes in your life that could impact the size or timing of your need for your money. Take your annual review seriously and really think through what you want for the future well in advance of needing money to get it. If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there (thanks Lewis Carroll). But if you do know where you’re going, you have a map, you have the right vehicle for the bumps you might encounter, and you have the help of someone who understands the road, there’s a pretty darn good chance you’ll make it.

As always, if you have any questions, please feel free to contact me.