Switching to a new Q&A format for most blog posts as I think it makes them easier to read and allows me to include questions that clients have asked. If you have more questions on a related (or really any topic), please let me know and I will try to include them in future posts.

Q. What is this post about?

A. The economic, financial market, and personal finance impact of the “coronavirus” (covid-19).

Q. Aren’t there more important impacts from a viral outbreak than those related to finance?

A. Yes. It’s not lost on me that there are much greater concerns in public health than in finance when a viral outbreak hits. I am sensitive to the tens of thousands of people who are sick and the thousands who have or will die. My job is in finance though, so I will leave the health and social issues to the experts in those fields and focus here on my scope of knowledge and understanding.

Q. How has covid-19 impacted financial markets?

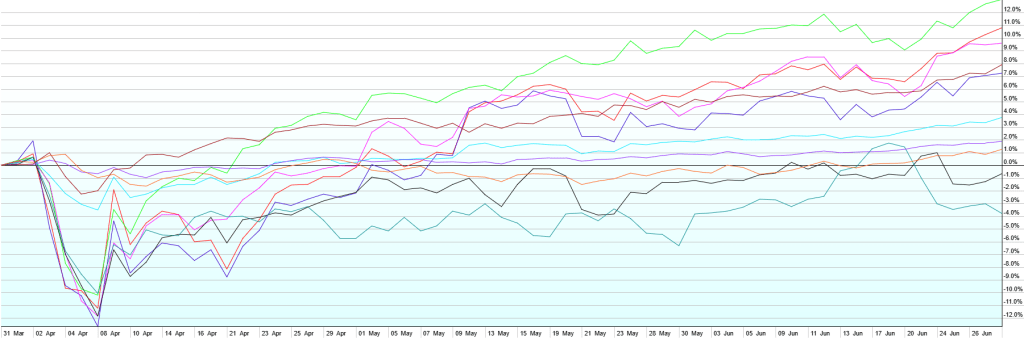

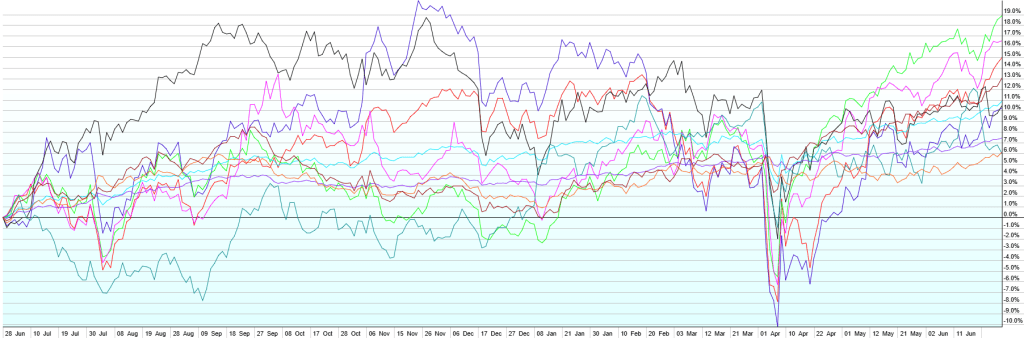

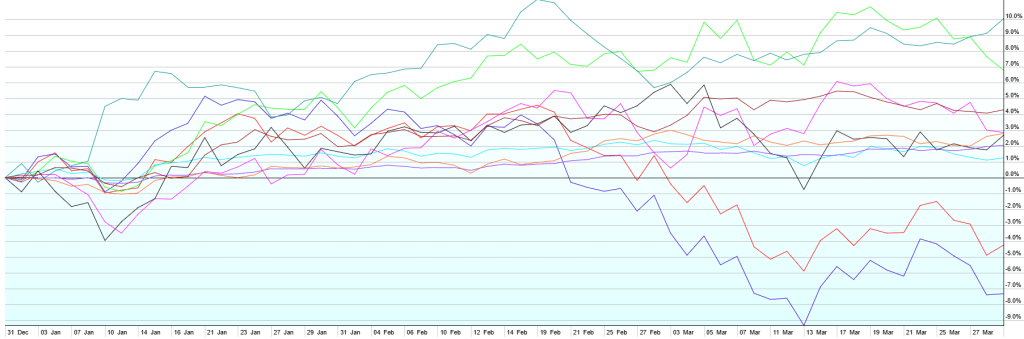

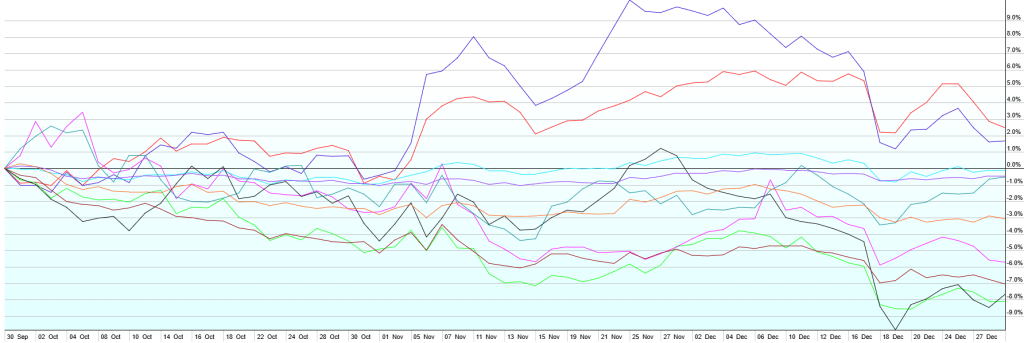

A. The impact of the Coronavirus (covid-19) on financial markets over the past week has been sharp and swift. Long-term interest rates have fallen sharply (US 10-year treasury hit an all-time low today of 1.243%) causing bond values to increase, while stocks around the globe have fallen. On average, stocks are down about 10% over the last week around the world, with some areas, sectors, and asset classes down much more than that.

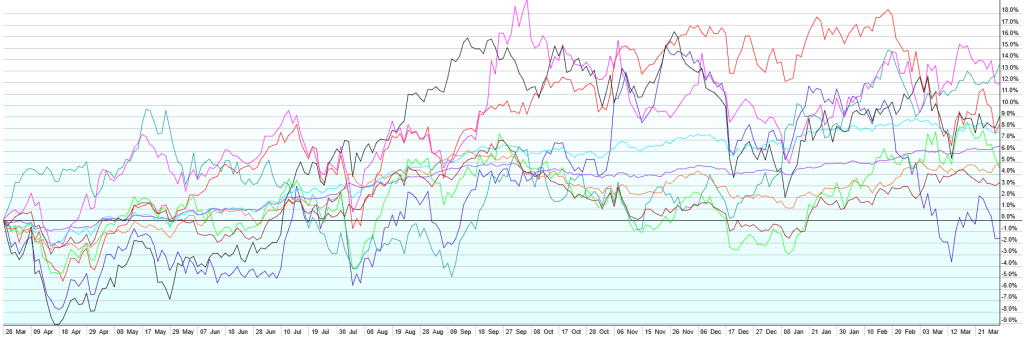

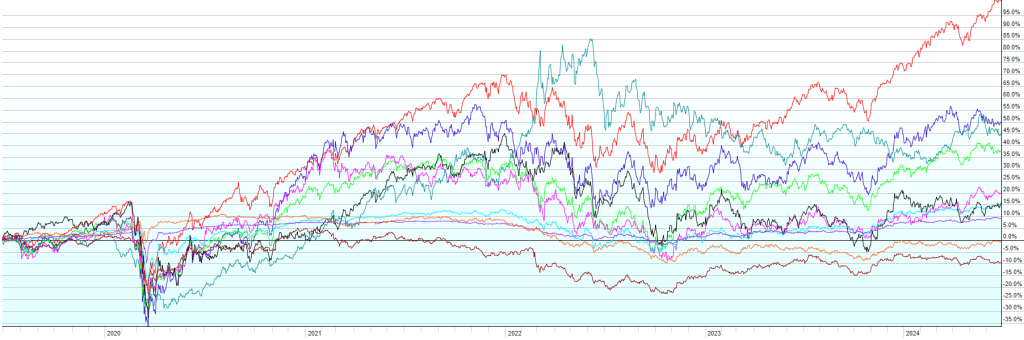

Q. We were just at all-time highs though, right? So 10% from all-time high isn’t so bad is it?

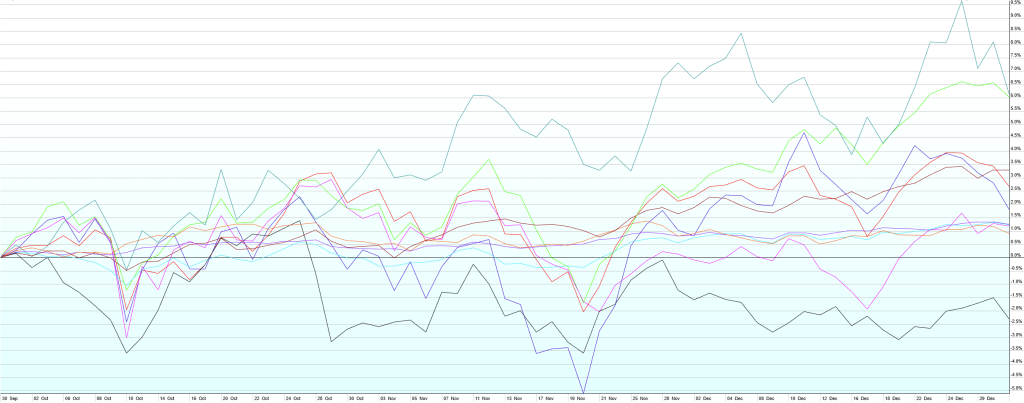

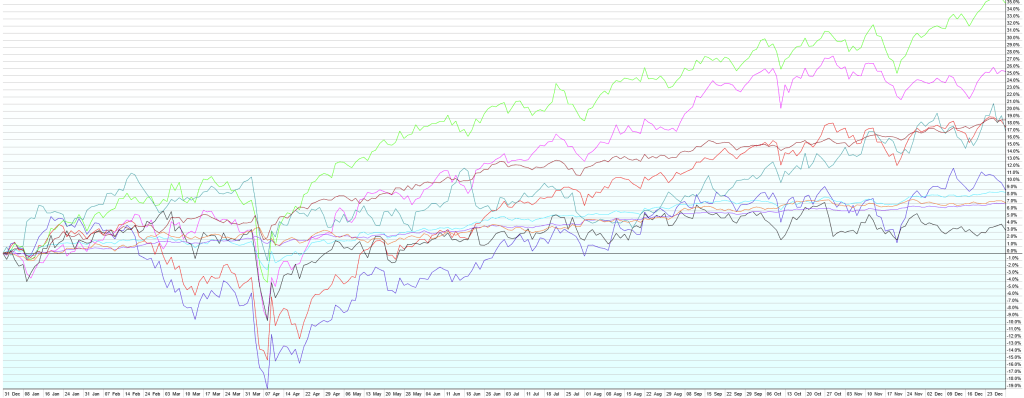

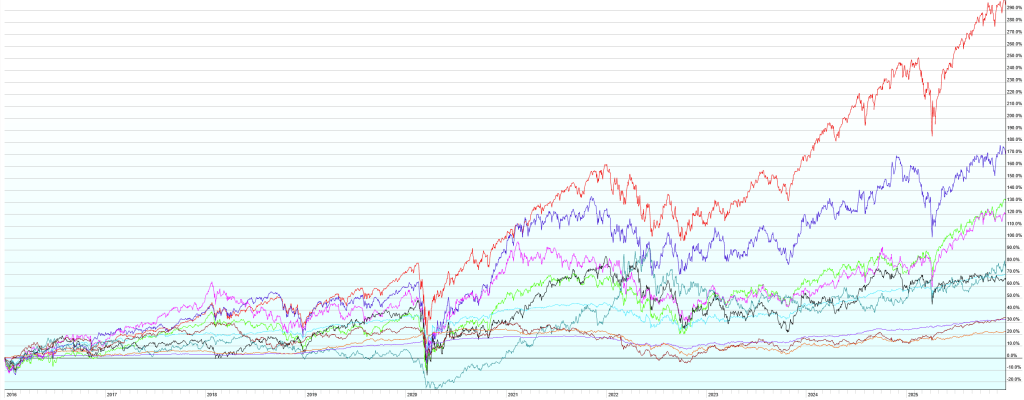

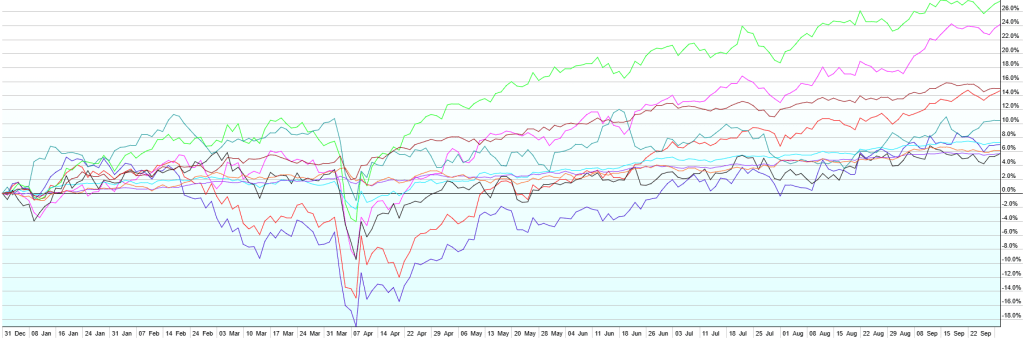

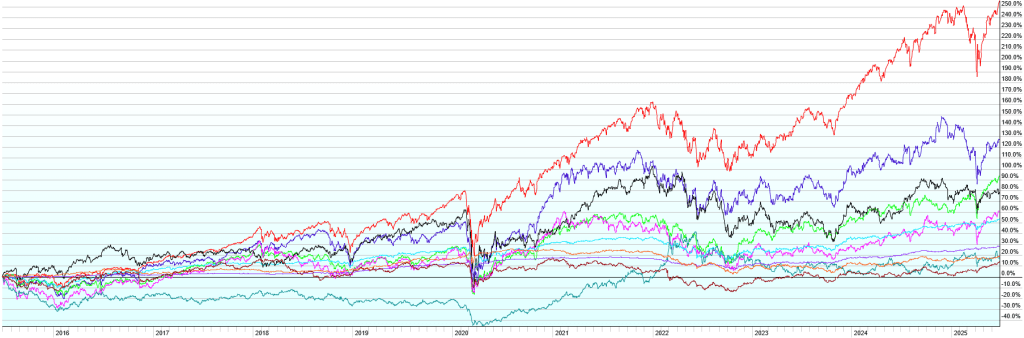

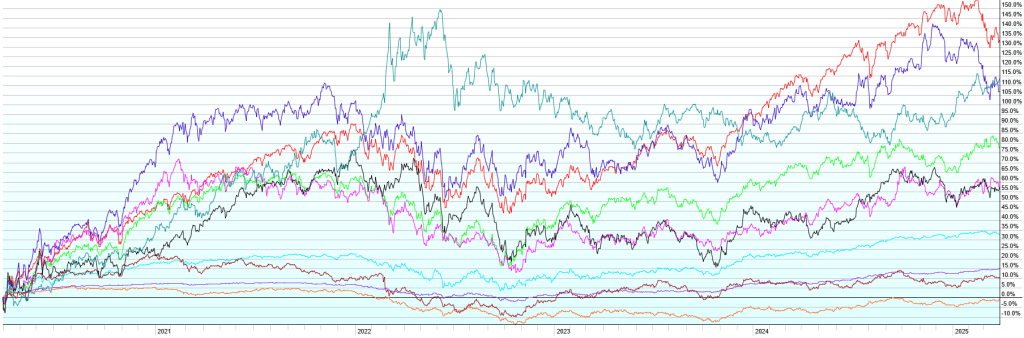

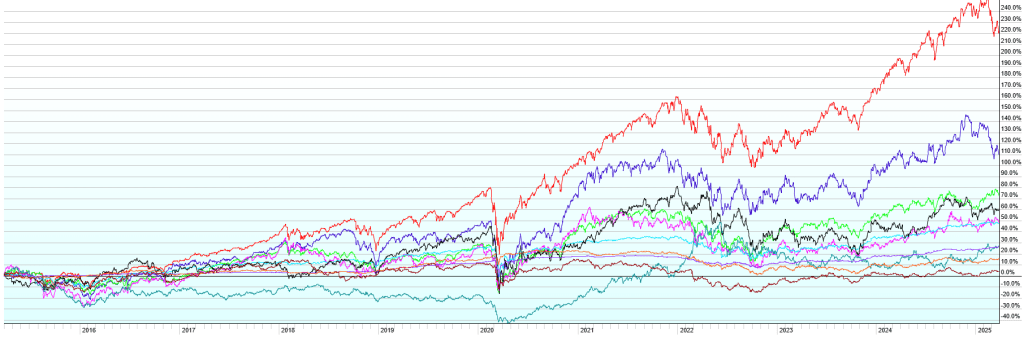

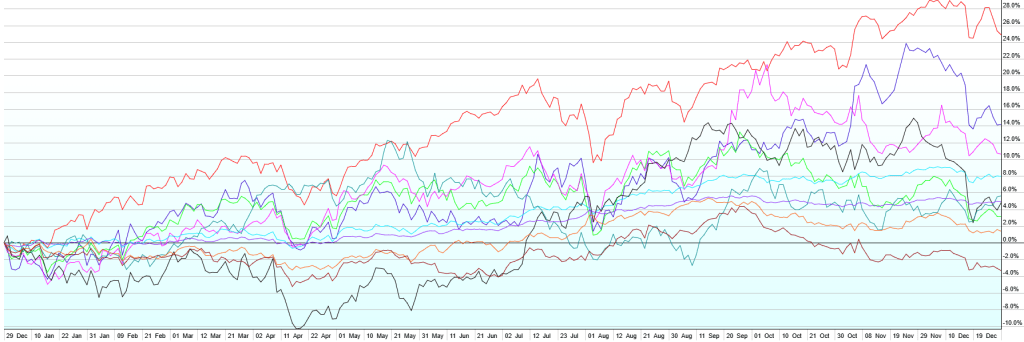

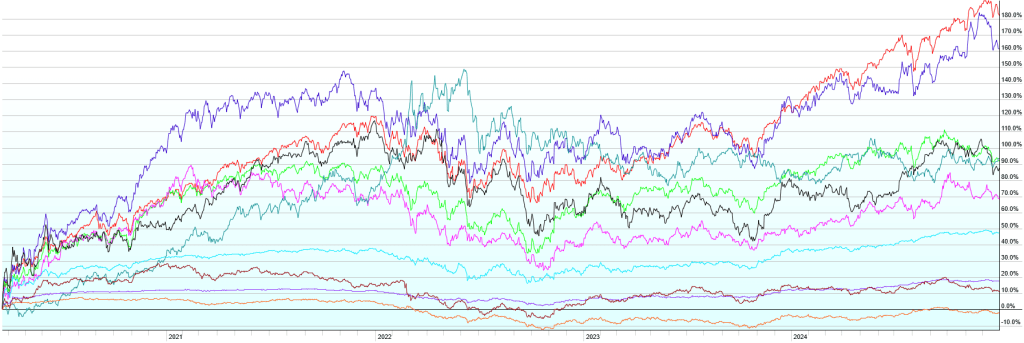

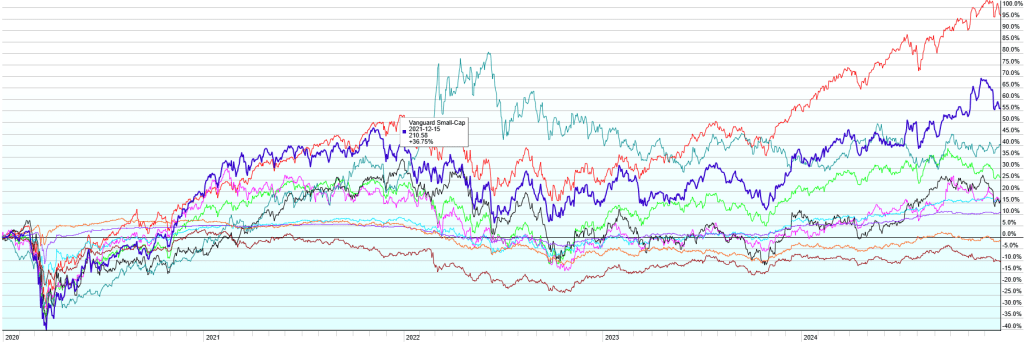

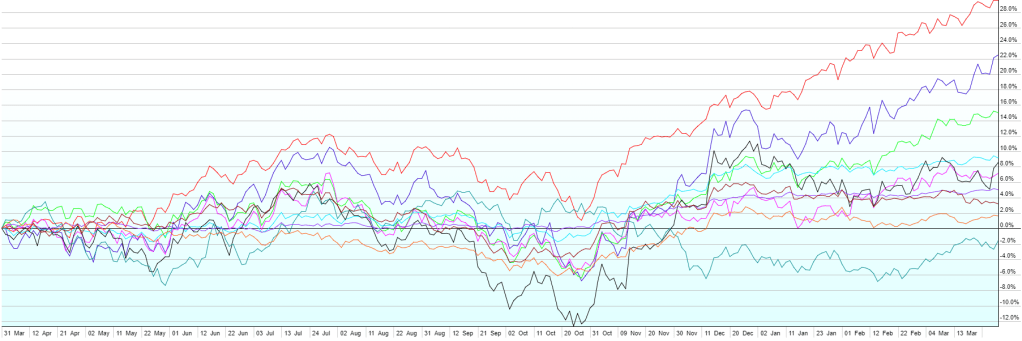

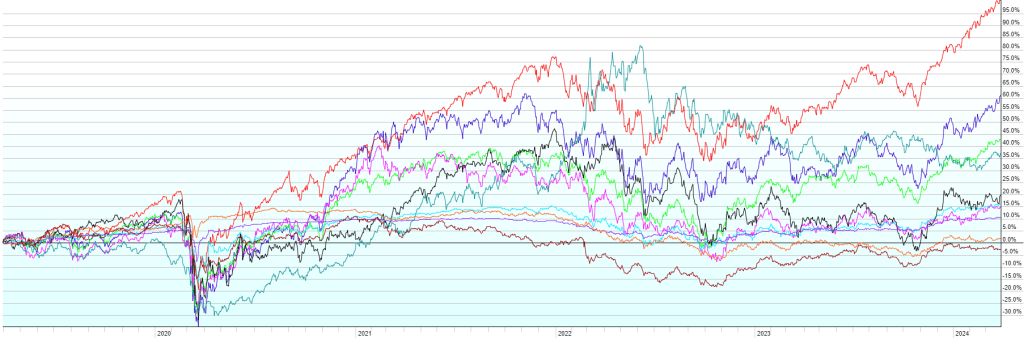

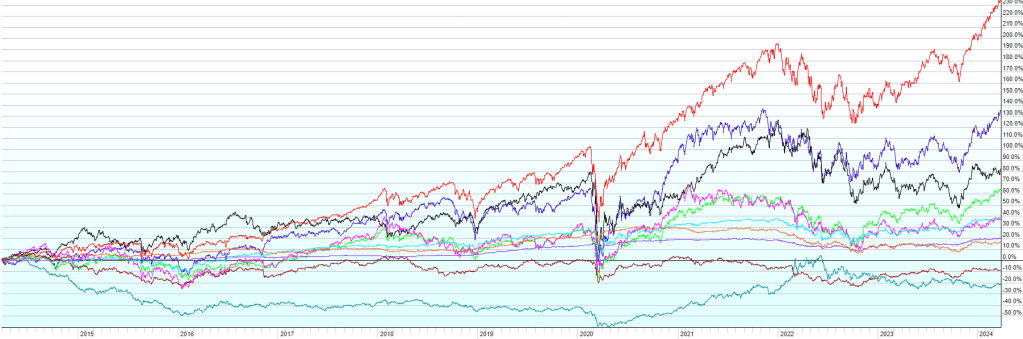

A: The well-publicized S&P 500 was recently at an all-time high, after a year with very high returns in 2019, so 10% down only puts the index back to where it was last fall. But in other areas of the market the impact is worse, even in the US. Small cap stocks still hadn’t exceeded their highs from August 2018, even with the great 2019 year, because of how sharply they were down in Q4 2018. They are now down 14% from their all-time high. Small-cap value stocks are down 21% from their high in Aug 2018. Outside the US, stocks peaked in Jan 2018. Developed markets are down 16%, while emerging markets are down 20% from their all-time highs. Perhaps this correction will finally end the perception that all stocks have been moving straight up since 2009, which was simply not true, even before the covid-19 impact.

Q. Why is this virus having such an impact on stocks?

A. It’s mostly fear of the fear of what’s to come. That is, fear of a sharp economic downturn led by public fear of the virus. If people stop traveling, eating out, shopping, etc., due to worries about catching the virus then those part of the economy grind to a halt. If people can’t work in jobs that require physical presence, then those businesses will be impacted as well. If aggregate demand for products falls, then manufacturing is also impacted. Slowly, a population that is afraid to leave their houses, causes widespread economic distress. That leads to layoffs, less spending, and the usual downward spiral that comes with economic recession. Again, it’s the fear of fear that is causing the stock market to panic and price in lower earnings and an economic downturn. For the most part, it is not that those things are actually happening (at least not to a large degree inside the US). There are also overseas manufacturing issues, predominantly in China where the virus seems to have originated back in December and where 78k of the 82k currently confirmed cases exist. Those manufacturing issues cause inventory dislocations (shortages of some things, too much of other things) which also hurt businesses and can cause product shortages and other supply chain disruptions.

Q. Wouldn’t all of that be temporary though?

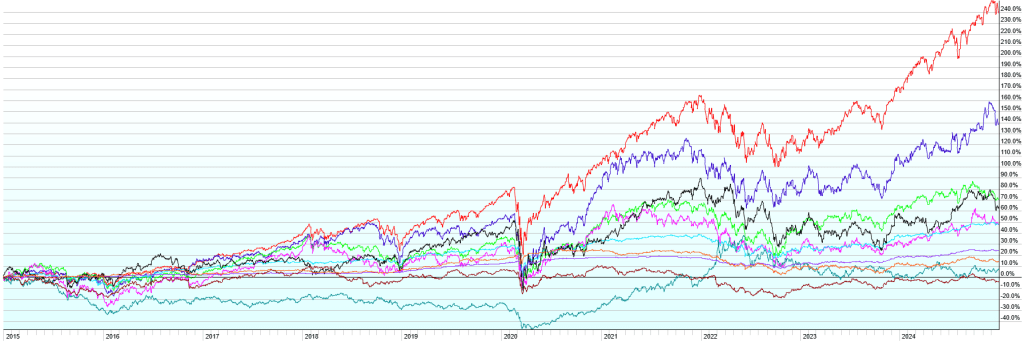

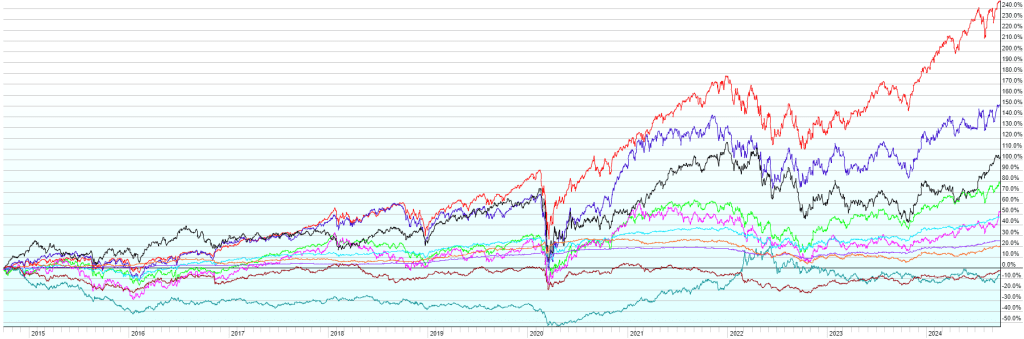

A. Likely yes. Though we don’t know how long “temporary” is. Unless the virus is so bad that it kills a significant portion of the world’s population, it’s hard to believe there will be long-term economic impact. But, there is a lot that is unknown about the virus at this point. Even if its death rate isn’t high (currently running at 1.65% outside the China with 55 deaths out of 3,332 confirmed cases), it could become a constant part of society like the flu, which could cause some drop in overall productivity. What makes temporary economic downturns dangerous are the massive debt levels that exist in both the public and private sector around the world. Debt payments continue to be due even if revenue (tax collections for government, sales for businesses, wages for individuals) declines or stops. That risks default or bankruptcy, layoffs, reduction in government services, lower consumer spending, etc. Still, over the long-term aggregate demand would return. While individual businesses may fail, when aggregate demand returns, businesses that survive + new businesses pick up that slack, hire those people who were laid off, and return to growth. Take the airlines for example. Their stocks are getting pummeled by fear of virus impacts. If those impacts are bad enough, it’s possible that debt-ridden companies could have a liquidity or solvency crisis and be forced into bankruptcy or out of business. But the airlines in aggregate, likely have to fly the same number of people from point A to point B once aggregate demand returns. So you’ll have winners and losers, but in total, no long-term impact. That makes massive, industry-wide stock declines seem irrational. Better said, if the long-term outlook for earnings remains unchanged, then even if earnings temporarily fall and a few companies fail, true value of the industry as a whole remains unchanged. On a larger scale, this is why PWA uses extremely diversified portfolios rather than picking individual stocks. We don’t know the future winners or losers (covid-19 didn’t even exist 3 months ago) so we don’t bet on individual companies. Instead we invest in the global economy as a whole, which has a very high probability of growth over the long-term.

Q. Aren’t stock prices already high? Couldn’t this drop just be because prices were overvalued before the virus hit and were just looking for a reason to correct?

A. While some sectors and individual company valuations seem high, the stock market, even at its peak, was not excessively valued in my opinion. To value a stock, you have to look at future earnings and interest rates. With interest rates near historic lows even before the virus impact, stock valuations were fair. The S&P 500 for example was priced at about 18x 2020 projected earnings (which were high given the virus, but again, virus impacts are highly likely to be temporary). That’s a 5.55% earnings yield. In other words, if you put $100 into the S&P 500, its companies in aggregate give back $5.55 of earnings per year. Some of that gets paid out to you in dividends and some of it gets reinvested in the company to produce growth for the future. In contrast, the US 10-yr treasury was yielding ~1.5%, and cash was yielding even less than that. Would you rather have 5.5% per year in something with growth over the long-term (even if comes via a rollercoaster ride of ups and downs) or 1-2% of year steady?

Q. What about the Federal Reserve? What are they likely to do if there is a temporary economic shock due to the virus?

A. The Fed says they’re monitoring and stand ready to act. The market has gone from forecasting a moderate chance of one 0.25% rate cut in 2020, to a likely chance of two and maybe even three. Lower rates help to support the economy, ease debt burdens, provide more borrowing opportunities, and push more people toward investment rather than savings, all of which stimulate the economy. I’ve heard people say that rate cuts can’t cure the virus so they won’t help, but that’s not logical. Rate cuts stimulate economic activity. If the economy is depressed, regardless of the cause, then rates cuts will help offset that depression somewhat.

Q. How bad is this virus?

A. No one knows for sure, and certainly not me. I’m not a doctor or virologist (didn’t even sleep in a Holiday Inn last night), so I’ll stay away from the health impact. We also don’t know the real number of infections, though the reported number is about 82.5k worldwide, mostly in China, but with a rapidly growing number of cases outside China (453 two weeks ago, 1200 cases a week ago, 3332 today). We’re told that the virus has a 10-14 day incubation period, though some people may present sooner after exposure, and that it’s possible people might be contagious even during the incubation period (before symptoms present). If that incubation period is 14 days and the number of cases outside China has increased almost 10x in the last two weeks, it feels like a safe bet that 14 days from now there will be a lot more cases worldwide. In the US, there are currently 60 confirmed cases, with the majority coming from those who have been repatriated from overseas. Your guess on whether the other cases have been contained or not is as good as mine, but in a deeply interconnected world and cases multiplying in places like Europe and Japan, the probability of seeing more cases in the US seems high, whether they come from domestic or foreign exposure. Symptoms reportedly range from virtually nothing, to flu-like symptoms, to much more severe breathing issues and complications due to immune response. I haven’t seen any reporting on what those infections in the US have looked like. We do know that the time to recover varies widely, ranging from a couple of days to several weeks. Maybe the only upside to more cases in the US will be more understanding of the virus actual does, how it works, how it spreads, and how long it takes to get better if you catch it.

Q. Ok, so it’s likely to spread, we don’t know how bad it is, it has killed people, the mere fear of it might cause a recession, and company earnings are likely to take a hit… Are you selling everything?

A. Definitely not. The right answer in this case is to stick to your financial plan. I’ve said numerous times on this blog and in conversations with clients that stocks will almost certainly fall 50% from their highs at some point in our lifetimes (it happed twice from 2000-2009). I’ve also said that we will not know what the cause is or that it’s going to happen, until after it begins. And, we’ll never know when the market is down 10% or 20% whether the correction is over and we’ll get a sharp bounce back up (like in Q4 2018), or if it is just beginning of a 50% downturn (like in early 2008). The ideal strategy is not to try to predict the impact of the unpredictable. It’s to invest in a way that you don’t need to make predictions to be successful in achieving your goals. If you are in a place in your life where you need most of your available money soon (retirement funds if retired, education funds as your children near college age, or liquid funds for whatever reason), then that money shouldn’t be invested all in the stock market. On the flipside, if what happens over the short-term doesn’t matter, then you are far better off ignoring short-term impacts and invest aggressively, in stocks, for the long-term. Both of these are emotionally difficult, but it is how PWA manages portfolios for our clients. If a 10% market correction concerns you, then you’re either invested too aggressively for your goals or you’re letting emotion get in the way of rational thought. PWA is not selling any stocks in client portfolios due to covid-19. On the contrary, we will be selling bonds and buying stocks as the value of stocks fall. We did the opposite as stocks rose and this rebalancing provides a natural buy-low-sell-high rhythm over time.

Q. You always say that unless the world ends, everything will be ok over the long-term. What if this virus is, in some sense, the end of the world?

A. At the risk of waxing too philosophical, we can’t live life preparing for the end of the world. If the world ends and you’re the most prepared for it, do you get anything out of that? Similarly, we can’t invest for the end of the world. He who dies with the most money does not win. Given the infinitesimally small chance that this becomes a cataclysmic event and the fact that your assets won’t have value in a post-cataclysm world anyway, it seems to make a lot more sense to plan for life to continue in its current state for many more generations. Remember also that the intersection of your sphere of concern and your sphere of control is where you should spend your time. Epidemics and doomsday predictions (as well as stock market performance) may be something that worry you, but they are most certainly not things you can influence. If you disagree with this answer, let’s discuss. There are definitely ways to plan for the end of the world, irrational as it may seem. It’s just far from my baseline strategy.

Q. So what should I be doing at the intersection of concern and control?

A.

· Interest rates have fallen pretty sharply. Mortgage rates are at all-time lows. If you own a home and haven’t refinanced recently, check with your lender, another bank, and/or a mortgage broker to see what you can do. Often, taking a slightly above market rate (but still below your current rate) lets your lender give a credit that covers most/all closing costs. That makes the benefit of refinancing happen almost instantly, rather than having to wait for the lower interest payments to offset a high amount of closing costs. Optimizing this is dependent on your individual situation.

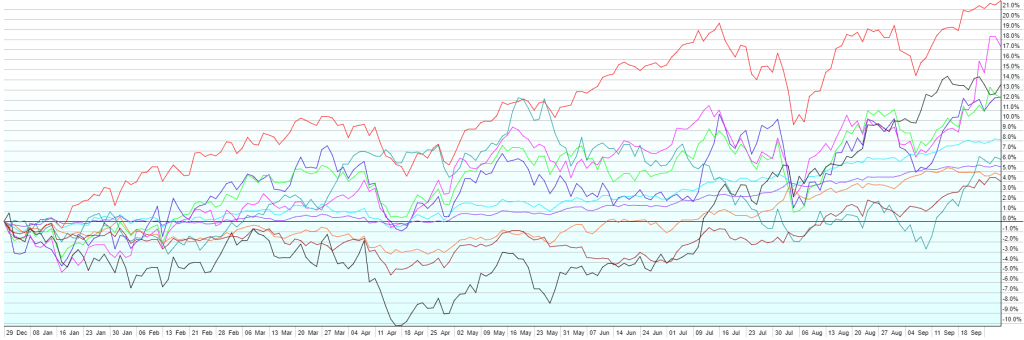

· If you’ve been sitting on cash waiting for the market to fall to deploy it to more useful investments than a savings account, here’s a 10% pullback. It doesn’t mean it won’t go to 20% or even 50%. It just means it’s 10% cheaper than a week ago. If you’re not ready to pull the trigger, put a plan in place to pull the trigger based on something certain so you keep emotion out of it (e.g. I will add 20% of my excess cash to my portfolio every 5% down in the market). Don’t get me wrong… having your money always invested is a better mathematical answer, even if it means investing a large lump sum. But if you just cannot get yourself to do that, investing something slowly is better than nothing at all.

· On the flipside, make sure you have an emergency fund of 3-6 months of expenses in cash plus any short-term spending that is needed and won’t be covered by income. People tend to let this slip in the good times because they’re always getting bonuses, commissions, etc. and there’s not need to pay attention to cash levels. Be wary of the not-so-good-times.

· Some temporary economic damage is highly likely. There will almost certainly be job losses. We haven’t lived through that in a decade. Unless you can afford the job loss, make yourself indispensable at work.

· I know I said I’d stay out of the health-related advice, but I can’t resist this one. Stay informed, but from factual sources. Listen to the CDC. (You can also find infection statistics, updated daily, from John Hopkins CSSE). Wash your hands. Try not to touch your face. Be wary of misinformation or fear mongering from those who profit by keeping your attention (i.e. anyone who sells ads). And, I hate to say this, but It’s an election year and while we hope our leaders put politics aside, their careers depend on your feelings. Incumbents have a bias toward making the situation seem better than it is. Challengers have an bias toward making the situation seem worse than it is. Keep that in mind and try to listen to more than one source of information before reacting to anything.