Just because tariffs aren’t another reason to panic doesn’t mean they aren’t going to cause angst. To be clear, I think they are a policy error and the way they have been implemented is a huge (trying hard not to do Trump voice in my head as I type that) policy error. I try to stay out of discussing politics, esp. in large audiences, because no seems to have an open mind and 50% of that audience will almost certainly hate whatever I’m saying (probably more like 90% since I consider myself politically homeless… not aligned with either of our two choices in political party). I will preface this post by stating that if you believe Trump is the United States’s savior and that he can do no wrong, you should probably not read the rest of this post. If you believe everything Trump has ever said or done or will ever say or do is wrong, evil, etc. you should probably not read the rest of this post. If you’re somewhere in the middle, and have an open mind, this post is for you! There won’t be any facts, figures, and charts in this one. I’m just going to try to explain what’s going from my point of view, because more than one client has recently asked my opinion. I suspect that means more of you are wondering what I think. If you’re not, feel free to skip past this one. There isn’t any financial advice here… just some plain English ‘splaining. I’ll try to stop before it turns into a pure ramble.

Last week, the administration announced “reciprocal” tariffs on just about every country in the world. (Aside: I don’t really care that they included an uninhabited island… it’s dumb, who cares, it has no impact on anything). They call the tariffs reciprocal because they believe those countries have unfair practices in place that disadvantage the US on trade. It’s hard to argue against that point en masse. At least in some cases, some countries have disadvantaged some vendor, product, or sector of the US. A common large scale example is the intellectual property theft in which China has engaged for decades. A more specific one might be the very high tariffs (as high as 110%) that India imposes on foreign made autos. It would be hard work to research each and every unfair trade practice from the bottom up and quantify how to reciprocate in a fair way. So, the administration has chosen a different approach. They’ve decided not to target unfair trade practices, but instead to define unfair as running a trade deficit with the US. That is, if a country exports more goods to the US than it imports from us, there must be something fundamentally unfair there! To “fix” the unfairness, we’re going to impose a tariff equal to the other country’s trade surplus with us divided by their exports to us, minimum 10%. That is, (exports – imports) / exports… in their view it’s the unfairness ratio. To be nice (/sarcasm), we’ll actually only make the tariff rate half this amount.

Calculations aside, I think the president and his team have a fundamental misunderstanding of the economic order of the world. If you were to rank all the countries in the world In terms of wealth and opportunity for wealth, it seems to me that the US would be pretty high in those rankings. To threaten the world economy with extreme “reciprocal tariffs” as a way of equalizing trade imbalances just makes no sense to me. Have the third world nations where the average person lives on the equivalent of a few dollars per day really stolen our wealth and opportunity? Trade imbalances imply specialization and the movement of resources to their optimal locations to make production efficient. I have a trade imbalance with my grocery store because I’m not good at farming and they are good at stocking their shelves with food. They can specialize in running a grocery store and get things cheaper and more efficiently than if I had to do it myself. I’m happy to pay them for that and free up my time for more productive things which I can do better when I’m not hungry. Allowing specialization and removing trade barriers makes things more efficient. We should be working with other countries to eliminate all tariffs (slowly, over time, so as to not shock any particular portion of the global market) and other trade barriers to establish free and fair trade around the globe. All economies will benefit from that and the global economy will grow as a result.

Targeted tariffs or subsidies, esp. as part of negotiation for fair trade deals makes sense to me. Even the threat of escalating tariffs for countries that refuse to negotiate or be more fair on their end could have a place. Financial markets seemed mostly ok with this as well. Life could go on with a few tariff snipers taking aim at unfair practices and the threat of a tariff bomb if those unfair practices continued. Thinking that we could, or that we’d even want to, eliminate all trade deficits, is not a solution. To make matters worse, massive tariffs imposed all at once, will shock global trade. While the importer pays the tariff, it’s likely that some of it gets passed on to the American consumer, some of it is eaten by the importer, and some of it is negotiated through to the exporter in a lower price on their end. All three components feel some pain there. That’s fine with surgically applied specific/strategic tariffs. With globally applied tariffs at high rates, there will be demand destruction on top of the pain. That is, fewer goods are going to be sold pretty much everywhere in the world because of dramatically higher prices. Strategic sourcing or product substitution isn’t available if the tariffs are everywhere and on almost everything. Fewer goods sold means lower profits, on top of the squeeze that tariffs already put on profits. Lower profits means less global employment. It would be hard to envision massive job creation in the US if global jobs are shrinking. In other words, we’re trying to make our slice of the pie bigger at the expense of the size of the pie. Now multiply all of that by an unknown amount of retaliatory tariffs from other countries, which Trump has already said will be met with more reciprocal tariffs from the US.

If all of the above sounds unstable, imagine how it sounds to a CEO trying to plan where to build a new factory that will be completed in 5 years time. Not only does forecasting demand and pricing become more difficult, but they know that these newly announced policies are unsustainable. A trade war isn’t going to last forever. Where does the world land in terms of trade deals? What’s the impact on currencies? What happens after the next election cycle around the world? What will be the terms of imports and exports if they build a new factory in location A vs. location B? Can they even really afford to build a factory in such uncertainty? It sure does sound hard for all the manufacturing jobs to come back to the US in that scenario.

That brings me to my last issue with all of this. Do we really have an appetite for massive increases in factory work in the US? Where will the people come from to do these jobs, even if they are fairly paid? We won’t even let people come in from Mexico on a seasonal basis to pick fruit. And if they are fairly paid, are we ready to pay 5x and 10x the price for goods? It seems we’d be better off focusing on advancing technology (robotics, manufacturing processes, etc.) than trying to force clothes and electronics to be made domestically. Highly educated engineers using robotics to make something better than an iphone in a way that is even cheaper than offshore labor could built… that sounds like a better way to drive some manufacturing back to the US. Or maybe the manufacturing should never come back. Unemployment is 4%. Almost everyone who wants a job has a job. We buy other countries’ goods with our dollars and they take those dollars and invest them back in our companies and our treasuries. As Bloomberg’s Matt Levine recently wrote: “… a world in which the US gives people finance and gets back inexpensive goods strikes me as good for the US. We give them entries in computer databases, they give us back food and clothing: That is a magical deal for us!” Maybe, just maybe, our goal shouldn’t be to emulate the third world economies to try make our slice bigger, but rather to let goods, services, and capital flow freely so that it can continue to expand the pie.

The current policy is so egregiously bad that it just can’t stay put. I don’t think it’s malicious. I think it’s dumb and lazy. Either the Trump administration will shift to negotiating and ultimately say this was a negotiating tactic all along but they couldn’t tell other countries that… art of the deal sort of stuff OR Congress will take back the power to impose tariffs from the President and reverse this (they gave it to the President after all) OR Trump will throw someone under the bus, blame them for poor implementation, say “you’re fired” a la The Apprentice, and modify the approach to “what I really wanted to do from the beginning”. Trump has been talking for decades about the trade imbalance and now has set out to fix the problem. The problem though, isn’t the trade imbalance. It’s his understanding of economics.

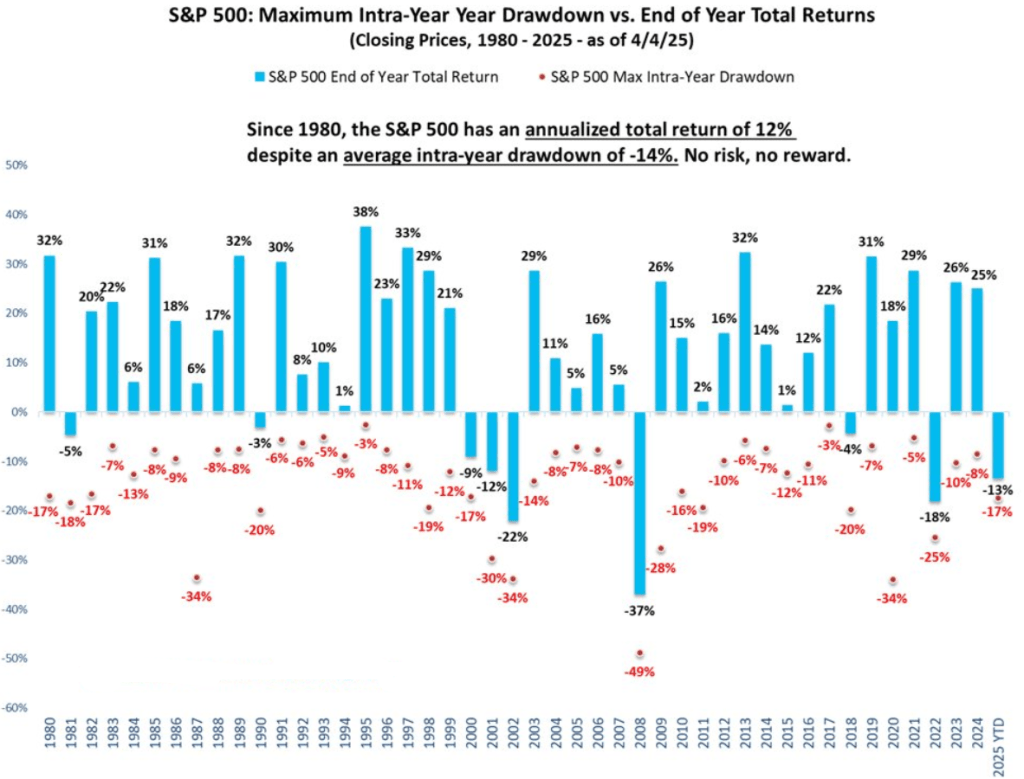

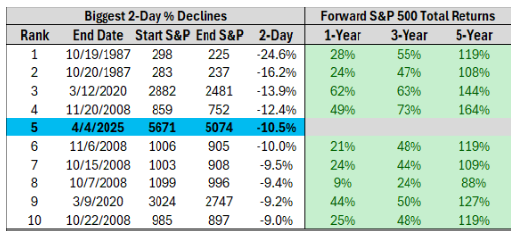

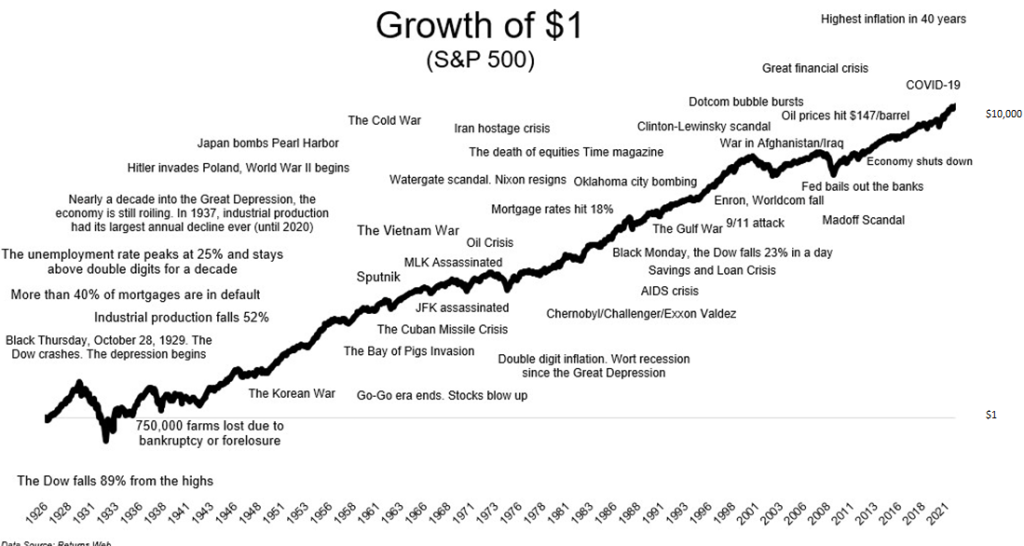

In the short-term, financial markets price assets and liabilities on emotions, running through the fear and greed cycle, which determines current supply and demand for the assets. In the long-term, they price assets and liabilities based on future cash flows. If poor economic policy disturbs global trade for a few weeks or even months, it will eventually get back to normal. I mean, it did with covid when almost the entire world shut down for a few months. People are still going to fly in airplanes. We’re still going to eat. We’re still going to buy clothing. We’ll still need cars. Kids will be born and raised. And all the while the smart folks will be inventing new things and moving the world forward so it can be more productive. I’m confident that the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad, tariff policy isn’t going to end the economic world. In fact, the worse financial markets get, the more pressure builds on the administration, the closer we are to de-escalation. It didn’t have to be this way, but the good news is that it won’t always be this way.